So much is written about imposter syndrome – but little of it is clear on what is being talked about.

Almost every client I have spoken to has said that, at some point, they have experienced a feeling that chimes with what many people call “imposter syndrome.” This is regardless of their seniority, background, or identity. But the name is where the similarity ends. It’s ranged from something they can brush off as a momentary discomfort, to debilitating fear or paralysis.

So much is written about imposter syndrome – but little of it is clear on what is being talked about. If a wide range of different feelings get put in a big box marked “Imposter Syndrome” – are we assuming that everything in that box is the same?

One of the fundamentals of coaching is that we are all able to change and to keep growing, to find our own solutions, if we know ourselves – our feelings, behaviour, perceptions, and contexts. We are all unique. I want to help and support that as a coach – no client’s exploration and thinking about what to do with their imposter feelings and to move forward, is ever the same. So, I am on high alert when anything one person is feeling, is assumed to be the same as someone else.

Many well-known figures have spoken about imposter syndrome – from Maya Angelou, and Tom Hanks, to Sundar Pichai the CEO of Google, the former COO of Meta – and Einstein[1]. The descriptions seem to sometimes overlap — but are they talking about one thing?

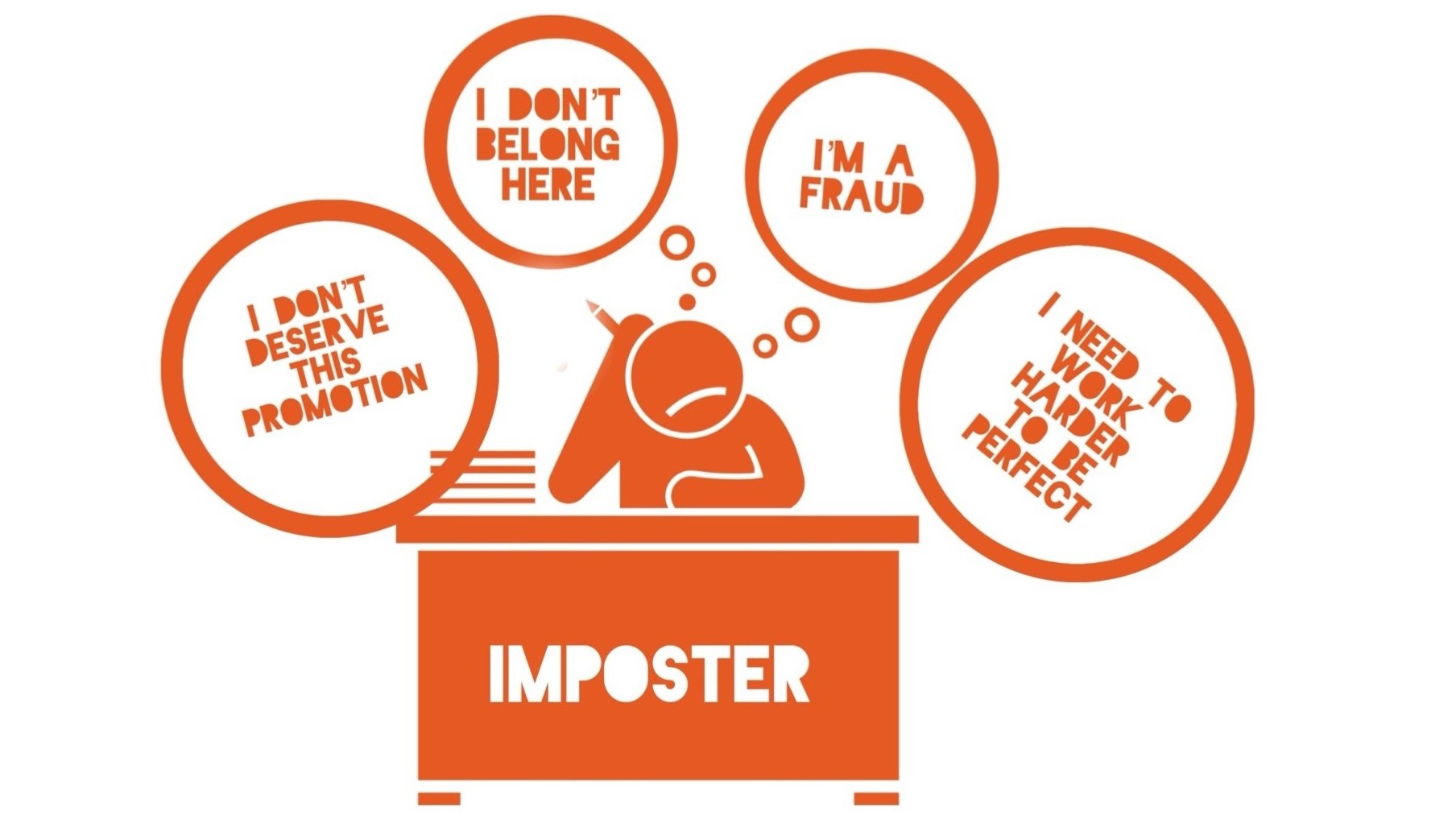

They seem to be describing a range of feelings – some environment-specific, some experienced all the time. Feeling you are a fraud, and a constant fear of being exposed as a fake. Feeling you have deceived others about your abilities. Feeling out of place due to gender, race, or background, or being “the only one” in your field. Feeling you do not belong in certain environments – that you are an outsider due to this environment. An inability to internalise your success. Disbelief in deserving your achievements – despite extensive proof or acknowledgement. And perfectionism, feeling you need to be the best, like a superwoman/man.

Academics have made attempts to clarify, or at least to narrow down, the definition of all these differing feelings in the imposter syndrome box. Some of their research is misquoted – such as “82% of people experience imposter syndrome at some point” This figure comes from a study [2] that cites the range as between 9% and 82% – varying widely depending on how those studies were conducted. The same piece of research looked at 62 peer reviewed studies and confirmed very widespread reporting of imposter syndrome – across ages, genders, and race – and negative impacts on individuals and their work. But it concluded that despite the widespread reported feelings, there was no uniform clinical evidence base to rely on when it came to treatment. It recommended more acknowledgement by employers, and more research into treatments.

Last month a new review of what we know so far was published[3] which really digs into that one-size-fits-all, one-label box of feelings, and examines a few assumptions about imposter syndrome that are often stated, but appear to be – well – wrong?

No, a better definition would be not always right.

Basima Twefik from MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), and her partners, confirmed a lack of consistency in terms and methodology, and suggested that assumptions might be holding back helpful lines of enquiry and a better understanding of Imposter Syndrome. Needless to say, “more research is needed” was the conclusion.

But they highlighted several common assumptions that are made – which their review concluded do not add up. –

So, these feelings are not always permanent, not always just a problem with an individual who needs to be “fixed,” they do not seem to happen in isolation, they can be experienced by anyone, and they are not necessarily a bad thing.

There is no simple take away giving us new tools to navigate these feelings or self-perceptions, commonly grouped as imposter syndrome.

But I like that the study warns us off assuming there are simple definitions and traits – that therefore have simple answers. And I like that we are nudged towards an individual’s context or work culture or individual circumstances.

Because it shifts the focus back to us, our own individual selves, and our own unique responses. The learning and self-awareness of what is happening to us, uniquely, can become clearer, and with that clarity, we can decide what do – if anything. It removes the pressure of misquoted statistics, comparisons to other people, or getting tangled up in solutions that are not relevant to how we feel.

I can tell you I will have some “Imposter Syndrome” about posting this blog – I am not an academic researcher. I will notice it, and think about it, and know that doing anything that puts a focus on me personally is uncomfortable – and I will remember why that is. Then I will post it anyway, because I have had a life of journalistic inquiry, and the experience of thoughtful humans who have brought different feelings from that box marked “Imposter Syndrome” to work and to coaching. and I have read the new study, and I want to share anything that might help people feel self-empowered.

You might want to think about whether the term imposter syndrome is helpful to you. Perhaps there is another, more precise way to notice what you are feeling, and when it shows up, and in what environment. That way you have your own unique data set to work with and so find your own unique way to thrive. As leaders, if we can talk about and acknowledge the range of feelings experienced by individuals and teams in the work environment, we might also find we can be change agents to make our workplace culture one that help everyone thrive too.

[1] https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2005/02/28/time-bandits-2

[2] “Prevalence, Predictors, and Treatment of Impostor Syndrome: A Systematic Review” in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, Bravata et al. (2020)

[3] Workplace Impostor Thoughts, Impostor Feelings, and Impostorism: An Integrative, Multidisciplinary Review of Research on the Impostor Phenomenon The Academy of Management Annals 19(1):38-73 Jan 2025

This blog was written by Leadership Coach Karen O’Connor. Karen brings insight into navigating change and empowering teams, from 30 years of experience as a Senior Leader in the fast-changing media content and news industry. Her style is direct – with careful listening, empathy, and challenge.

+ 2 more

Communication and Leadership Coach. Confidence and clarity as an empowering leader.